What Do We Carry At Golden Legend?

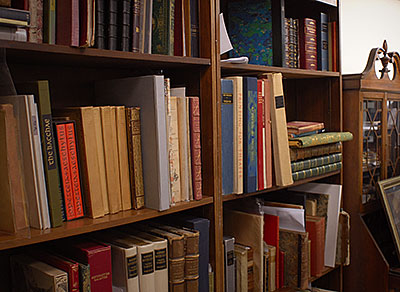

Out of print and rare editions on dance, theatre, music, and stage design & costume. Also, we offer original letters and manuscripts, drawings, sculpture (occasionally), and prints including old-master prints from the 16–18th centuries. Most of our general inventory is listed on this website on the database page.

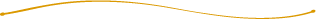

We also have finely-printed, limited-edition, and beautiful art books as we have for many years. At present, we have books bound by Therese Moncey, P.L Martin, Zaenshdorf & Co, as well as Rivière. We have original art books by Picasso, Braque, Segonzac and others. We also have finely printed books by the Golden Cockerel, Cranach, Allen, Circle, Gregynog.

About Gordon Hollis

Gordon Hollis, President, has an A.M., University of Chicago; has been a member of the ABAA/ILAB (since 1984); member of Board of Governors, 1992–3; and President of the S.C. Chapter of the ABAA (2004–6). He is a member of the Grolier Club, Society of Dance History Scholars, American Society of Theatre Historians, and Bibliographic Society of America.

Before becoming a bookseller (if he can remember the dim past), he taught English at Metropolitan State College in Denver (his alma mater for his AB) and at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

He has published short stories and poetry (again in the dim past). In the last few years he has published two books and a number of articles, listed below.

John Ward and his magnificent collection

Publisher and editor (2010)

The Bonel Collection

Rare and Beautiful Books

Editor and publisher (2003)

A catalogue of this important collection of first editions, beautifully bound books and livres d’artistes.

Oral History : Gordon Hollis, Golden Legend (2010)

Antiquarian Book Collecting in Southern California (2007)

Article

Some Americans in Paris: Our Trip to the Paris Book Fair 2009

Article with Kate Fultz Hollis

Opinion: The ILAB Bookfairs - For all members or only the wealthiest? (2009)

Article

Still a step ahead

Isadora Duncan's daring alternative to the strictures of ballet put the value on expression and awakened creative impulses in others. A trove of materials reminds how singular she remains.

Lewis Segal | Times Staff Writer (2005)

Partial subject

A Worldwide Diaghilev "Museum": Collecting, Collections, and Centers of Research. (2009)

Moderator panel discussion on rare Diaghilev material

Harvard University

festschrift for Peter B. Howard (2010)

contributor

Memberships:

|

Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America |  |

International League of Antiquarian Booksellers |

This year marks the 30th year of Golden Legend, Inc. We were first located on Melrose Avenue and then at 7615 Sunset Boulevard for sixteen years.

In the ten years since we left our open shop on Sunset for our bright and sunny office on South Beverly Drive in Beverly Hills, our business has changed greatly as has the rare book business in general.

These days, email is an essential part of life, almost replacing the telephone and completely replacing the fax machine. Our research routine includes consultation of the web for its databases and links to digitized books. We buy research books via Amazon and often pay via Paypal.

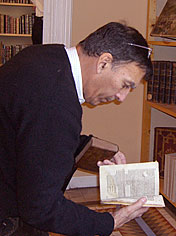

During the growth of the internet, we asked many times whether the physical book is still needed. With virtual texts and digitized manuscripts coming into general use, we wondered if the old or rare book is necessary at all. Why not use a facsimile of a 17th century book instead of the original?

The simple truth is that the text is only part of the book although the most important part—the soul, if you will. The body of the book is unique with each copy of an edition having its own unique history. After some time, two copies of the same edition will take on different characteristics at the hands of their previous owners. One will now bear astute notes and comments, or perhaps a loving inscription, or maybe a beautiful new binding; another will suffer through flood or fire or a knife (perhaps at the hands of a censor). Perhaps the book will be restored with pages from a later edition (with differences in the text). It should be obvious that we have much to learn from each book that comes down to us when we understand the effects that centuries of use can and must have on a book.

Although Golden Legend receives book orders via the internet, sometimes from complete strangers, we have actually met most of our customers—certainly our regular clientele. Many have come to us via book fairs or through our lists and catalogues (over 300 issued since 1981). We have known some of our regular customers for over twenty years: one the head of a major German ballet company, another a dance critic from Tokyo.

Others like the curators of the the New York Public Library’s Dance Division and the Harvard Theatre Collection have been customers and friends for almost thirty years. In this day of vanishing bookshops, we still have visitors come to our “rooms” regularly. Instead of retreating to an “at-home” operation, we have just renewed our lease here on South Beverly Drive.

Freed from regular hours, we are at liberty to travel more than ever. In recent years we have been to Tokyo, Paris, Milan, Barcelona, London, and many major cities in America to call on clients and to exhibit at book fairs. Our relations with other dealers stretch from Sweden to Italy to Argentina to Japan, making it easy to import books from around the world. These trading relationships are particularly important when a buyer wants to examine a book before making a commitment. He simply comes in, sits down, and looks at the book to his heart’s content. If he doesn’t want it, we simply send it back to its source.

An Antiquarian Adventure

A few years ago, I acquired a 17th-century manuscript written by Pierre Paul Sevin of Tournon, France who was a painter, draftsman and designer of festivals in the mid-17th century for the Catholic Church. His festival designs included the canonization in 1666 of St. Francis de Sales attended by Queen Cristina of Sweden and many notables from around Europe

I knew the manuscript was genuine because of comparisons with illustrations of Sevin’s work from museum catalogs. I actually went a step further to show the manuscript to the old-master print expert at the Bibliothèque Nationale who spent all of four minutes authenticating it after I had hand carried it to Paris from California.

To show the way our small community of antiquarians work, I will recount a happy story.

Two years ago, I received a polite email from a graduate student in Lyon asking if I could photocopy the manuscript for his use because he was doing his dissertation on Sevin. I politely refused for several reasons, including the probable decline in value in the unique original after a copy became available. This young man was not so easily discouraged, indicating he could not come to California to see it because he had commitments working at an art museum in the suburbs of Lyon as a curator and teaching art history at the University of Lyon. He stressed the scholarly need for him to consult the mss because—after all—his entire dissertation was about Sevin.

Out of guilt, but also with an understanding of the basic reason for having rare material in the first place: to share it with those who need to study it, I wrote that I would send the manuscript for him to read if he could ask his University Librarian to receive the manuscript and safe-keep it for a month or so. No photocopying allowed. He quickly arranged for the rare book librarian at the Bibliothèque Municipal de Lyon to take charge of the manuscript. Off went the manuscript via FEDEX. A month later, he emailed that he had finished reading it. The manuscript was promptly sent back, with a thank-you note that included an invitation to see Lyon.

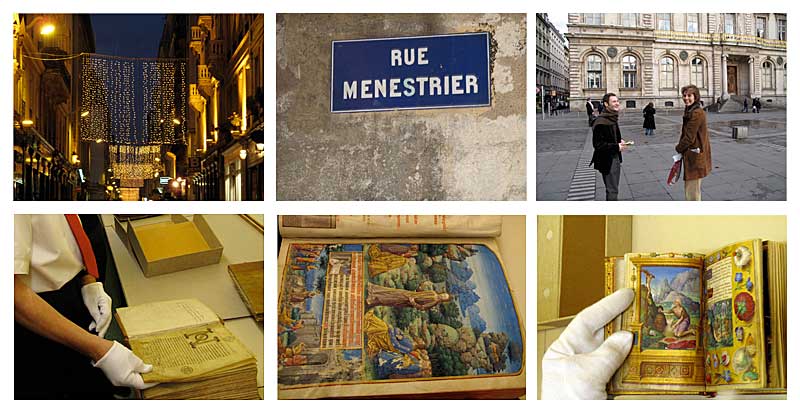

Last year as my wife and I were planning a vacation (and some working visits for me) to Europe, we saw that our route would take us close to Lyon, so we wrote to ask if we could meet our scholar and if we could see the rare book collection at the world famous Bibliothèque Municipal de Lyon where some of the earliest European manuscripts are held. As the photos show, we had a wonderful time and spent several hours looking at treasures that we would never have seen had it not been for the “cultural exchange.” We were then given a wonderful tour of Lyon (including its world-class bouchons).

What is an antiquarian bookseller & what does he do?

ANTIQUARIAN

A person who collects, studies, or sells valuable old things—called

also antiquary.

In Thomas Hardy’s novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles in the opening scene, the town parson, an amateur antiquarian meets Jack Durbey to declare that Jack is from a celebrated ancient Normal family. Here begins the tale that ends with the fall of Durbey’s innocent young daughter Tess.

Parson Trigham’s research, correct or erroneous, leads him to a conclusion based on evidence from the past, in this case from tomb inscriptions. An antiquarian bookseller has a similar job of identification when he discovers an antique book: identification, description & authentication, plus the added task of evaluation.

Given the many hundreds of thousands of books printed before the modern era (roughly the period of 1820-1840 where books began to printed on machine-made paper, bound by mechanized binding machines, and illustrated with lithographs or photographs which afford very large press runs), the bookseller needs great experience and careful research. Antiquarian books can be very individual due to the many past owners over the centuries and also due to early methods of printing and binding which made no two books quite alike. Our job is to account for the variations of typography and text within issues and later editions of books, changes of format in at the hands of binders, and of owners who have annotated, sophisticated, decorated, added to and even mutilated their books.

Like many booksellers, I have handled both modern and antique books over the years. During the last decade, I have gravitated towards the antique, especially early-printed books (16th through 18th century), because that is where the challenges are. Rarely a week goes by when I don’t encounter an early-printed book that comes as a complete surprise to me because I have never seen anything like it before or because it is a hitherto unknown variation of what I thought it was. Working with early-printed books is slightly like hiking up a mountain to find wild-flowers, plants, and animals that are like those I have seen before but with variations or, on occasion, wholly different.

First identification:

In order to make my living selling antiquarian and modern books, I must identify, describe, and value the items that I offer. Sometimes, when I offer something I have had previously, my job is made easier because the identification is routine. Other times, weeks or even months are needed to identify and describe an item. Evaluation or pricing is part intuitive and part based on comparison. For particularly rare books, comparisons are crucial but sometimes unobtainable.

Here are some examples of the process:

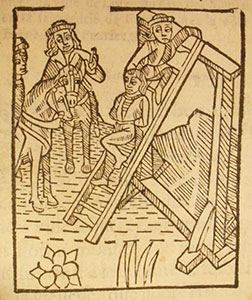

Recently, I bought and sold a bound volume that collected early 17th century canards which are French small, printed pamphlets describing marvelous and horrifying events that supposedly took place in their time, like the comet that was seen in the night sky in early 17th century Provence. When it struck earth, a fire-breathing dragon emerged and was seen running through the hills setting farms on fire until it was killed by an assemblage of brave farmers. So it was faithfully reported. Another canard tells of the brutal murder of a French girl by invading Spanish soldiers who were finally brought to a fitting justice (with a woodcut illustration showing them being hanged).

While there is much written about the role of the canard in the development of the modern newspaper and also the renaissance novella little data remains to identify their editions or account for their overall numbers. As a result, I didn’t know which editions I had of these often reprinted pamphlets (which were taken by peddlers from city to city), nor could I write intelligently about how many canards were printed.

Ultimately, I located a 1964 bibliography done of the canards by the then Conservateur de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France which identified several of mine and documented the 517 titles located in the libraries of France (mentioning that many more were probably published but now lost). Because of this research, I sold the volume to Johns Hopkins University and received a second inquiry from the Newberry Library.

Creating a context for a book or manuscript from multiple sources:

A few years ago, I acquired a manuscript diary of one Sir William Breton, (whose known dates were only 1763–1773) of London who habitually recorded the name and location of every play he attended during the year but not much about his life, friends, or professional associations. This love of theatre was commendable, but I needed to find out more about the compiler and his relation to the these plays. Was he a critic or an author? I had no idea and could not readily find much in the reference sources at hand.

One inclement weekend, while I was visiting the campus of the University of Illinois, I spent most of the weekend in their fabulous campus libraries and emerged with a fairly full biographical picture of Breton actually Bretton (b. ca. 1720 d. London 1773), an English courtier who spent most of his life in service to Augusta Princess of Wales and George III. I also developed an idea of the historical value of the diary because it added a great deal of information about Bretton’s relationship to the politically important Lord Bute (whose box Bretton often used). Finally, the diary vividly portrayed the character and activities and interests of Bretton, who can only be described as an English “courtier” of the late 18th century whose dilettante interests, life of privilege, and dutiful service are vividly documented in the diary. Ultimately, I offered and sold the manuscript to Harvard University’s Houghton Library.

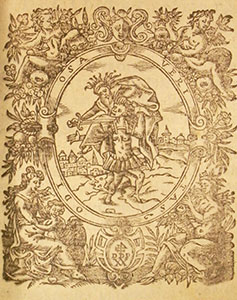

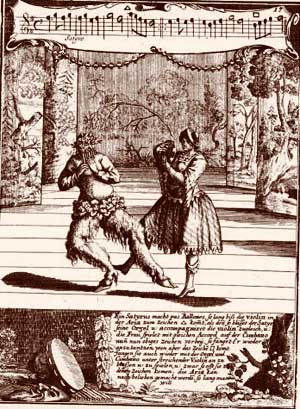

Guarantee and authentication:

The question of guarantee and authentication often comes up in world of book selling because books and manuscripts often have lost their provenance or chain of ownership. One example of these problems comes immediately to mind. A few years ago, a German colleague offered me an 18th century book on dancing that was known for its beauty and its rarity: Gregorio Lambranzi’s Nuova e curiosa scuola de' balli theatrali (Nuremberg, 1716) complete and beautifully illustrated and in fine condition, although in modern binding. I immediately found a prospective client, the New York Public Library’s Dance Division. The Library wanted the usual guarantee that the book was complete, but they also wanted the guarantee that book was not stolen or “liberated” from a German institution after World War II. Concerning the completeness, this was a relatively simple matter. The pagination matched identically with the copy at the J.P. Getty Research Institute here in Los Angeles and also with the few known copies listed in the bibliographies. A careful examination of the pages showed they were all printed from the same stock and all showed the same amount of use. As the book was in a modern binding, no evidence was found of any insertion of pages from another copy.

Regarding the second guarantee, I was in a bit of a quandary about the book’s chain of ownership since records from German libraries were chaotic following the war. My colleague in Germany was also concerned to make sure that the book had clear title, so he contacted the last owner from Leipzig who was able to put the matter at rest by indicating that he had owned the book for many years and had published an exact facsimile of it in the 1980s. Since the facsimile was widely distributed, we concluded that the owner was not trying to hide anything and no institution had made any claim for the book in twenty years. As a result, we felt comfortable with its provenance; the New York Public Library agreed and purchased the volume.

Evaluation:

Concerning how books are evaluated, much of the value is based on comparisons, like any other type of object from houses on the Pacific Ocean to black truffles. A bookseller will spend much of his day looking at prices of other copies of the same book or similar copies if they are available through catalogues or via websites. Book-selling databases such as addall.com and vialibri.com index and include other databases aside from their own. In addition, records of books that have sold at auction—so-called “sold lot” archives are available through Sothebys, Christies, and the French auction controller Auctions.fr. Bancroft Parkman issues auction records going back to 1975 for U.S and some European auctions. If another copy of the book I am evaluating has sold at auction in 1982, for example, I may end up driving to the Getty Research Institute to look at the actual auction catalogue description itself.

Location & Hours:

Hours by appointment

Golden Legend, Inc.

11740 San Vicente Blvd Suite 109

Los Angeles, CA 90049

Tel: 310-721-3584

©2023 Gordon Hollis

©2023 Gordon Hollis